| |

1960s |

| |

2001: A Space Odyssey, Directed by Stanley Kubrick

Batman, Directed by Leslie H. Martinson

The Birds, Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Bonnie and Clyde, Directed by Arthur Penn

The Graduate, Directed by Mike Nichols

A Hard Day’s Night, Directed by Richard Lester

Hud, Directed by Martin Ritt

Lawrence of Arabia, Directed by David Lean

Midnight Cowboy, Directed by John Schlesinger

The Misfits, Directed by John Huston

The Passion of Anna, Directed by Ingmar Bergman

A Patch of Blue, Directed by Guy Green

Persona, Directed by Ingmar Bergman

Psycho, Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, Directed by Sydney Pollack

What Ever Happened to Baby

Jane?, Directed by Robert Aldrich

|

|

|

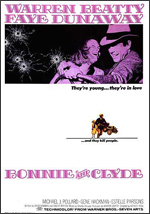

Bonnie and Clyde, Directed by Arthur Penn

Warner Bros., August 13, 1967 (US)

Screenplay: David Newman and Robert Benton, with special consultant Robert Towne

Starring: Warren Beatty, Faye Dunaway, Michael J. Pollard, Gene Hackman, and Estelle Parsons

Bonnie Parker, played by Faye Dunaway, opens Bonnie and Clyde pacing naked in her upstairs bedroom like a lioness on a hot tin roof, ready to pounce. When she eyes Clyde Barrow, portrayed by a dapper Warren Beatty, attempting to steal her mother’s car outside, Bonnie slips into a golden button-down-the-front dress, a pelt that blends with her blonde hair, and springs to the ground floor—not to shoo the thief but woo him.

After an amusingly brief flirtation lasting the duration of a walk into town, the duo establishes themselves as literal partners in crime: Their formal introduction occurs as they flee from a Texas neighborhood grocery store stickup that Bonnie goads Clyde into pulling. Turns out that consummating the coupling poses a greater challenge than an ill-conceived robbery at a Depression-era bank out of cash—one of their more amateurish and unsuccessful heists down the line—because Clyde’s carnal bankroll, metaphorically speaking, has also gone insolvent. Frustrated by the state of their non-affairs, Bonnie insults Clyde’s manhood.

Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway): Your advertising is just dandy. Folks’d never guess you don’t have a thing to sell.

An antithetical dig applies to the initial soft theatrical promotion of this landmark 1967 film. Warner Bros. mogul Jack Warner held such disregard for the picture that he supported a decision to short shrift advertising and bury the ostensible box office flop at inferior venues. Mr. Warner apparently suffered from performance anxiety, too, except for him, shoddy marketing obscured what turned into a commodity of riches.

Bonnie: Whew! You're good.

Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty): I ain't good. I'm the best!

Bonnie: And modest.

Audiences and discriminating critics rallied around the film, as passionately as detractors trashed it. The complete history is fascinating, but highlights include: preeminent critic for The New York Times, Bosley Crowther, losing his job in conjunction with a negative review (reviews, really, since Crowther practically made sport of smearing the film whenever he could); the opinion of another critic, the soon-to-be legendary Pauline Kael, an ardent defender (flaws and all), achieving induction in the pages of The New Yorker with her comprehensive assessment; and Joel Morgenstern, writing for Newsweek, denouncing the production, only to publish a revised positive critique upon a second viewing a week later. Support grew steadily and an uncommon re-release booked the controversial tale in premium theatres across North America well into a new year. Debate about the cinematic depiction of violence put the feature at the cultural forefront and on the cover of Time magazine, which, incidentally, originally panned the film. Ten Academy Award nominations pronounced industry acceptance. The response was schizophrenic and apt for a work of artistry that unspools maniacal by construction.

Bonnie and Clyde combines conflicting tones and styles in a virtuosic cinematic collage. Naturalism and artifice butt against one another, forging a sense of unease start to finish. Jarring jump cuts and continuity incongruities impede a seamless flow. Comedy and drama mesh within scenes. Delight and disgust clash in a single breath. The whole approach is purposefully inconsistent, and the emanating synergy has influenced filmmakers ever since its exhibition.

Over forty years hence, elements of the technique might appear less than revolutionary to the frequent moviegoer, largely because subsequent artists from Sam Peckinpah to Quentin Tarantino have pilfered the film’s repository, contributing to widespread recognition of the craft. A facet that remains consistently impressive, though, is how by the end credits, a somber silence, which echoes a break in the bouncy banjo picking formerly leavening the soundtrack, comes across as indispensable in processing the experience. The final about-face from frolic to solemnity hits with a potency and virility that only quiet contemplation helps contextualize. Whether it is the law, critics, or a general audience member, everybody requires a moment to catch up with the bandits on-screen and the ingenuity of the folks working behind the camera, who run with bold originality.

Clyde: You know what you done there? You told my story. You told my whole story right there, right there. One time, I told you I was gonna make you somebody. That’s what you done for me. You made me somebody they’re gonna remember.

In fairness to the unimpressed, to anybody descrying a limp cause for jubilation, the narrative does sporadically stray from the facts of real-life characters and events. Under different circumstances, stretching the truth conceivably marks a detriment. For example, if the film were an average biopic that stringently adhered to realism, the slightest exaggeration would emerge disingenuous. Nevertheless, an ethos of liberation set by the Swinging Sixties and the mood of a country entrenched in the complexities of the Vietnam War is relevant to consider. Embellishment fits enigmatic figures to a (stolen Ford Model) T, and myth embodies an integral part of why conversations get passed from generation to generation. In every regard, Bonnie and Clyde rises to the distinction of legend.

-MEG

|

|

|