| |

1980s |

| |

Blue Velvet, Directed by David Lynch

Body Heat, Directed by Lawrence Kasdan

A Christmas Story, Directed by Bob Clark

Dressed to Kill, Directed by Brian De Palma

Fitzcarraldo, Directed by Werner Herzog

Hannah and Her Sisters, Directed by Woody Allen

The King of Comedy, Directed by Martin Scorsese

The Natural, Directed by Barry Levinson

Ordinary People, Directed by Robert Redford

Planes, Trains and Automobiles, Directed by John Hughes

Polyester, Directed by John Waters

Repo Man, Directed by Alex Cox

Risky Business, Directed by Paul Brickman

Scarface, Directed by Brian De Palma

Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Directed by Steven Soderbergh

The Shining, Directed by Stanley Kubrick

The Times of Harvey Milk, Directed by Rob Epstein

Tootsie, Directed by Sydney Pollack

Trading Places, Directed by John Landis

The Trip to Bountiful, Directed by Peter Masterson

Witness, Directed by Peter Weir |

|

|

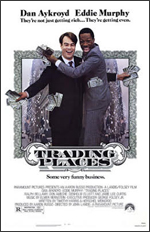

Trading Places, Directed by John Landis

Paramount Pictures, June 8, 1983 (US)

Screenplay: Timothy Harris and Herschel Weingrod

Starring: Dan Aykroyd, Eddie Murphy, Ralph Bellamy, Don Ameche, Denholm Elliott, and Jamie Lee Curtis

Randolph Duke (Ralph Bellamy): Poor, deluded creature. We caught him pilfering in our club, embezzling funds, selling drugs, and now he’s dressing up like Santa Claus. A very sordid business.

Mortimer Duke (Don Ameche): I can’t believe Winthorpe would fall to pieces like that.

What a change. Revisiting a film for the first time in thirty years is a dubious proposition, particularly considering first impressions were set during superficial youth. In the early ’80s, I was someone else. A kid. A punk. A know-it-all. One may surmise I am notably less a kid today.

Anyhow, I began the screening wondering whether my overall reaction would remain similar between then and now. Apprehension endangered delight because comedy often works on a temporal scale: Advancing age has a peculiar inclination to extract the ha-ha from life. On a basic level, though, I aimed to determine whether the film was holiday-themed enough for inclusion in a winter publication—far from an editorial mandate but a personal pursuit to compliment Yuletide cheer. The film’s original release date was in the summer, so studio honchos working on the picture must have reconciled their tie-in concerns, making them all the wiser. Anytime is really a fine time for laughs.

To my utter relief, the Christmastime setting surpasses the one I recollected. Images of a red Salvation Army collection kettle, St. Nick, ornamented evergreens, and patchy snow dirtied by Philadelphia traffic appear in quick succession, before the opening credits end. I somehow forgot that one of the main characters, Louis Winthorpe III (Dan Aykroyd), later dons a Santa suit riding on a public transit bus, drunkenly gnawing at a stolen salmon filet through a fake beard, after brandishing a gun in front of his former colleagues at their annual Xmas office party, as he hits an all-time low, stripped of privilege and framed for criminal acts by two villainous blue-blooded brothers, who formerly employed him. The scenario represents half of the plot’s light-hearted take on role reversal, examining social class through the study of nature vs. nurture. My drawing a blank on a significant chunk of detail was alarming, but, like the movie itself, this is not a tale told with a sparkling nostalgic shine, the spirit of miracles, angels, or purity. To my defense, an unsentimental tone explains the hazy advent association better than mental decay. Merry Christmas!

Seasonal worries expunged, a smile loosened my pursed lips … until other complications started accumulating. For instance, repeated flourishes of the word “faggot” and a deliberately appalling interjection of the unredacted version of the n-word sporadically sully the film’s goodwill. Charm freezes solid, when one’s thoughts skate off on a tangent regarding how, as a society, we are not presently compelled to abbreviate the disparaging term for homosexual males as “the f-word" in the same manner we prune the racial epithet. Granted, a different vulgarity starting with the letter “f” has already cornered the market; however, persistent repression of the LGBT community dolefully shares in the blame for tolerance.

Another uncomfortable occurrence involves Winthorpe emerging in blackface toward the end of the film. Whatever deliberation the filmmakers may have had on the subject at the time, I suspect a similar scene would not get filmed in 2014, going onto 2015. Oh, Happy New Year.

I reckoned with story inconsistencies during the re-viewing, too. For example, Winthorpe should have experienced a light bulb moment early on, regarding the identity of a mysterious figure, rather than delaying the realization until it was dramatically convenient. And since I am piling on, trepidation about the director and a tragic accident on the set of his previous film has only grown more horrid over time, lending additional pause. A brief pre-9/11 passage at the climax outside the World Trade Center sends a concluding shudder:

Louis Winthorpe III (Dan Aykroyd): Nothing you have ever experienced can prepare you for the unbridled carnage you are about to witness. The Super Bowl. The World Series. They don’t know what pressure is. In this building, it’s either kill or be killed. You make no friends in the pits, and you take no prisoners.

Broadcast versions have deleted the aforementioned dialogue in the aftermath of the attacks. As much as I am sympathetic, erasing even a slight portion of what is otherwise an enormously gratifying resolution resonates mishandling. No one predicted the future. Making a film stand accountable to forces unforeseen only covers up unfortunate coincidence. This is a movie in which the cast seems to have had a blast making, and their joy imparts upon the audience. Let it rest that we spin on a different world in the present-day without halting previous incarnations of our innocence.

An exchange from the film puts my mixed emotions into perspective. Billy Ray Valentine (Eddie Murphy, a bona fide star) dines at a posh, uppity restaurant, basking in his newfound status among the elite. Valentine lets an unguarded, seemingly inappropriate but truthful wisecrack about a couple at the table slip, creating an awkward silence. Then, one of the targeted individuals finally releases a howl. The action indulges the other guests to join the guffaw. The scene demonstrates that deferring to humor sometimes requires permission to laugh.

Fishing for approval to get past disquieting kinks this time around, my adult self switches places with that advantaged twerp, whose leg up was seeing the comedy unencumbered so many chuckles ago. Amusement, warmth, and glee emanate from the screen exactly as intended. Outside influences be damned. I conclude my experiment, assured no man remains altogether a product of his cynical environment.

A snicker breaks free, unfettered by second thoughts.

-MEG

|

|

|